What Is the Graduated Tuning Effect?

Your chanter seems to sound a bit flat in pitch. Or your Pipe Major says your chanter is “too sharp.” What is the first thing that many pipers will do?

The conventional technique is to take out the chanter and push or “sink” the reed further into the reed seat to sharpen the pitch, or raise it to flatten.

Pipers generally know that's what you're supposed to do, right? But did that solve the problem? How many pipers know that these reed movements primarily affect the top hand notes, with little effect on the bottom hand notes?

This difference in pitch change between the top and bottom hand notes due to moving the chanter reed is called the “graduated tuning effect.”

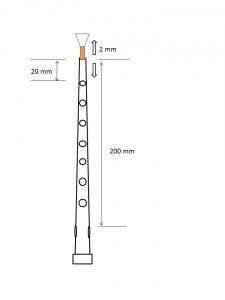

Using the diagram as a general reference, notice that the distance between the bottom of the chanter reed to the top of the high G hole, in this example, is 2 cm, or 20 mm. The distance from the bottom of the reed to the top of the low G holes is 20 cm, or 200 mm. Now, if the chanter reed is raised (or lowered), say, 2 mm, that difference represents a 10% change from the high G hole (2mm/20mm x 100 = 10%), but only 1% of the distance to the low G holes (2mm/200mm x 100 = 1%). Thus, the change in pitch brought about by moving the reed is significantly greater on high G (10%) than on low G (only 1%). This observation holds true for the other top hand and bottom hand notes as well. This observation does not mean there’s no effect on the bottom hand notes by moving the chanter reed. It is simply a difference in proportion of pitch changes, and this difference must be considered when fine tuning the chanter.

Some practical examples of how the graduated tuning effect should be used might be the following:

If the D is sharp to the other chanter notes, one way to flatten the D would be to raise the chanter reed, right? But doing so will simultaneously, and disproportionately, flatten all of the top hand notes, leaving a much bigger problem. On the other hand, simply applying a small amount of tape to the top of the D hole will flatten the D, leaving no effect on the other notes.

Another example might be that you have a flat high A, high G, and F. Now you know that sinking the reed will certainly sharpen these notes, but at the same time will have virtually no effect on the bottom hand notes.

Perhaps the most common real-world mistake? Let's say the bottom hand notes are flat (and the top hand is fine). The temptation is to sink the reed to sharpen them up. But, here we've actually made the problem worse! The top hand will now become even more sharp relative to the bottom hand. (As a side-note, this is why so many chanters around the world end up with way too much tape on the high hand notes!)

Recognizing the graduated tuning effect and applying its logical principles should help us all to improve our ability to more effectively tune our chanters.

Take Action

If you're a Dojo student, you can explore the graduated tuning effect more as part of our Transitioning to the Bagpipes course.

If you're not yet a Dojo Student, we'd love to welcome you! You can take the 11 Commandments course, which covers the 11 essential mindset tweaks you'll need to prepare yourself for mastery, or explore our monthly membership options and join us as a student, where you can learn more about this topic in a guided way with hundreds of other pipers around the world cheering you on!

Responses