Understanding Harmonics—Part 2

How many pipers have a firm grasp of the physics of sound that causes the unique and rich sound of our bagpipes? We are told that we should maintain a pressure in the pipe bag that is at the chanter reed’s “sweet spot”, that pressure that causes the reed to maximally vibrate and bring out the most “harmonics” and richness of sound of the reed. But what, really, are harmonics?

In Part 1, we explained how sound waves are described, and what they look like when analyzed visually. We also learned that musical instruments produce complex patterns of sound frequencies (pitch). These patterns of a single note include its “fundamental” frequency along with many harmonics, or overtones. Taken together the fundamental and its harmonics make up the timbre (pronounced “tamber”) of the musical instrument. In this post, we will explore the relationships between harmonics and a major scale, as well as how harmonics can be useful in tuning our bagpipes.

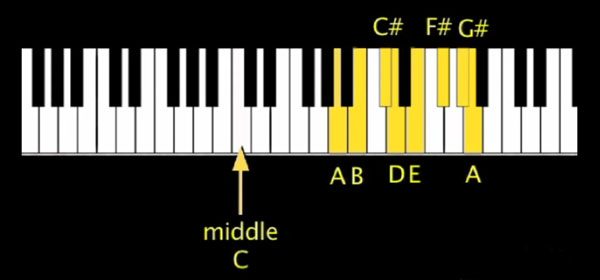

Much of modern music is made up of “major scales” for melodies and harmonies, including the music for bagpipes. A major scale contains eight tones, or sounds. Since we discussed in Part 1 different instruments playing the note “A”, we will continue using the A Major scale for our examples. It should be noted, however, that the following points can be used for any major scale. Figure 1 shows the A Major scale on the piano.

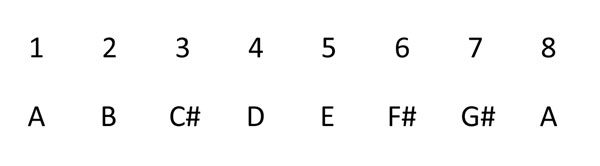

Each note of the scale can be given a corresponding number, so that we have the following:

The As at positions 1 and 8 are called the “tonic” note, the most important note because it names the A Major scale. The second most important note is the 5th note of the scale, also known as the “dominant”. Lastly, the next important note is the 3rd note, called the “mediant”. The 3rd note of a scale is what makes it a major scale. The tonic, 3rd, and 5th notes taken together make a major triad, or chord. Play Low A, C#, E, and High A on your practice chanter, and you will appreciate how each of those notes fit with the others in this major scale. These notes also constitute an A Major arpeggio. Understanding how different notes of a scale fit together is important for appreciating and writing harmonies.

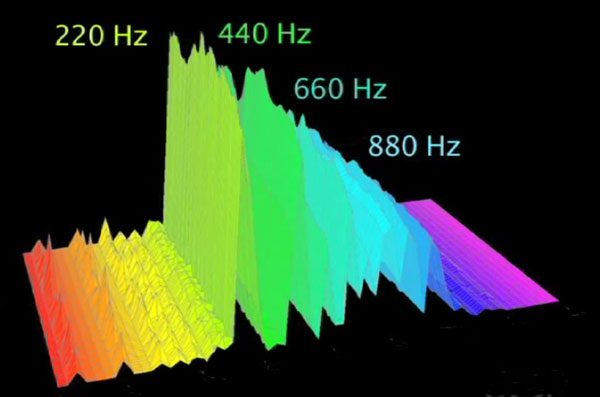

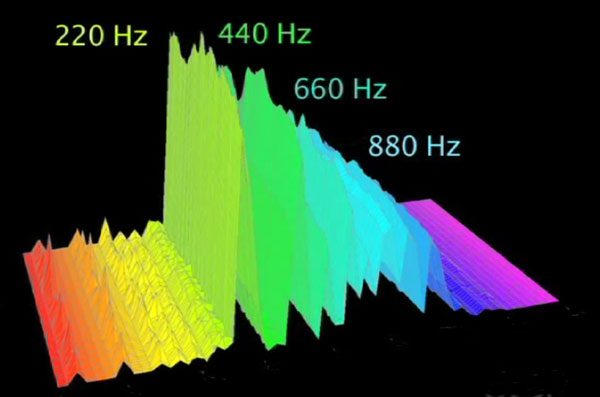

Now, what does knowing this information about a major scale have to do with harmonics? From Part 1, we saw that a cello playing the note “A” 220Hz is the fundamental note, while there are additional frequencies that are higher in pitch but lower amplitude. Some harmonics can be heard, while others are of such high pitch and low amplitude that they are beyond our hearing. See Figure 2.

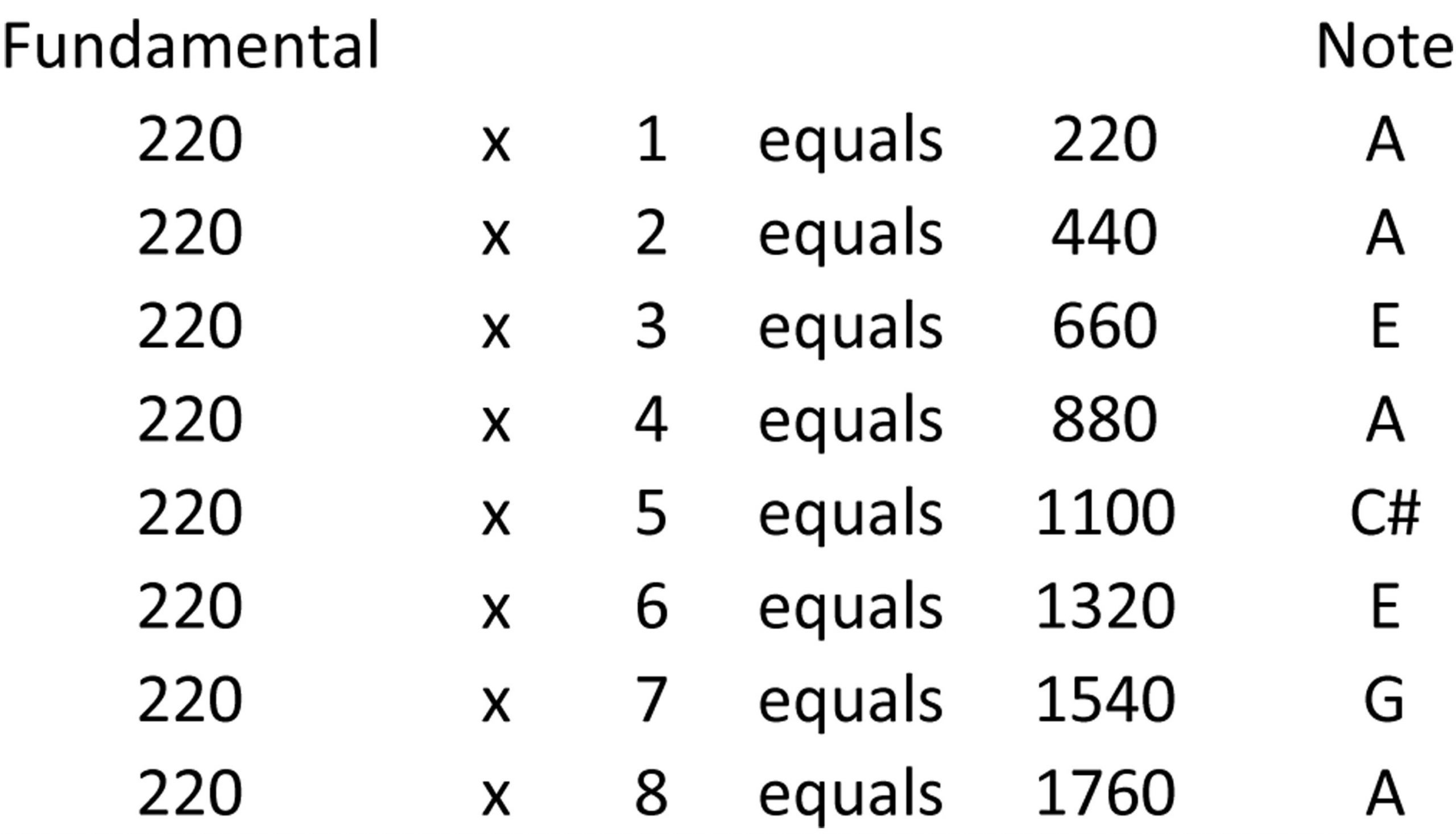

If one examines the fundamental frequency, and those of the harmonics, it can be seen that there is a clear numerical relationship between the fundamental its the harmonics. That relationship shows that each harmonic is a multiple of the fundamental’s frequency. The following table shows the “A” fundamental and its many harmonics:

Notice that the first note, the fundamental note A, has a pitch of 220Hz. The next note is also an A, but with a pitch of 440 Hz. The second harmonic is 660 Hz, which happens to be the note E. The third harmonic is yet another A, at 880 Hz, followed by a C# at 1100 Hz. The fifth harmonic is a frequency of 1320 Hz, and is another E. The 6th harmonic is G, with a pitch of 1540 Hz. The 7th harmonic is another A, but with a pitch of 1760 Hz.

The fundamental and the order of its harmonics are:

220 Fundamental

440 1st harmonic

660 2nd harmonic

880 3rd harmonic

1100 4th harmonic

1320 5th harmonic

1540 6th harmonic

1760 7th harmonic

Finally, let’s put our knowledge to work as it relates to the bagpipe. For the sake of this discussion, let’s assume that Low A on the chanter closely approximates concert A (440 Hz). Thus, the chanter has two As, Low A and High A (880 Hz). Further, each of those notes has its own set of rich harmonics. Now, when the tenors are tuned one octave lower than the chanter's Low A, the tenors’ fundamental note is A, but at a pitch of 220 Hz. Obviously, the drones produce their own harmonics. Finally, the bass drone, tuned to an octave below the tenors, has a fundamental frequency of 110 Hz. This low, but loud, pitch can be heard as vibrations of the bass drone reed. With four reeds in a bagpipe, each with its own harmonics, it is no wonder that a well-tuned bagpipe, played at the chanter reed’s sweet spot, sounds so incredibly beautiful.

At this point, we should not only better understand the science behind harmonics, we should also be able to appreciate the role harmonics play in tuning. For example, when tuning one tenor drone to another, we know that as the drones come closer together in pitch, there is a "warble" or "beat" produced. The closer the tuning gets, the "beats" become farther and apart, ultimately coming together and disappearing. If one keeps moving one of the tenors in the same direction, however, the "beats" will reappear. What is happening with the beats is that the fundamental frequency and harmonics of one drone are slightly out of synch with the other, so there is discord between the As. As the frequencies of one drone get closer to those of the other drones, the frequencies begin to line up on top of each other, which produces unison between the drones. If we listen carefully, as one tenor gets into tune with the other, the sound actually gets a bit louder because well aligned frequencies will reinforce each other, giving a slightly higher amplitude.

This writer again thanks Scott Laird, music instructor at the North Carolina School of Science and Math, for producing some outstanding educational videos that discuss the intersection of music and science.

Interested in learning more about harmonics, harmonies, and the production of sound?

Dojo U members can check out our Transitioning to the Bagpipes course for more information on tuning, or our Composing Fundamentals course for a deep dive on sound and harmonies.

Not a Dojo U member? Learn more about how you can sign up today!

Figure 1

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 2

Responses